Category Archives: Unusual deaths

Farm assist? A brief look at ‘tractor sex’

One of my good friends, Dr. Mike Sutton, recently sent me a story he’d come across with the headline “Suffolk man had sex with 450 tractors”. Given my academic interest in paraphilias and fetishism, I decided to try and track down the original source of the story and found that it was first published by the Suffolk Gazette back in 2015. According to the news report:

“Ralph Bishop, 53, was found by police with his trousers around his ankles “interfering” with a tractor parked in a field outside Saxmundham. He was arrested on suspicion of outraging public decency, and admitted to having had sex with around 450 tractors all over the Suffolk countryside. When officers searched his terraced home they found a collection of more than 5,000 tractor images on his laptop. The photos showed Bishop had a special desire for John Deere and Massey Ferguson tractors, particularly green ones. A police insider said: “We couldn’t believe it when we found him in the field. He was wearing a white t-shirt and Wellington boots and very little else. He was clearly in state of high excitement at the rear of the machine. Thankfully nobody else was around, but the field is close to a village primary school so we had to arrest him and educate him about the error of his ways. He told us he was particularly ‘in to’ axle grease and the presence of this around the back of tractors was all too much for him.” Bishop, twice divorced, was released without charge on condition he sought psychological help. He was put on the sex-offenders’ register. “He is also banned from the countryside and is now forbidden to go within one mile of a farm,” the police insider added. “So he has to live and remain in the middle of Ipswich to comply with that. However, we are watching him because we are worried about the safety of several street-cleaning machines.” Another policeman added: “He’ll also need to keep away from the town’s gardens – if he takes a fancy to a lawn mower he might find he loses more than just his liberty.”

Since the publication of this story, it has been re-reported dozens of times including the Daily Star and has even had follow-up stories (also in the Suffolk Gazette) – just type in the words ‘Ralph Bishop’ and ‘tractor’ and you’ll see what I am referring to. Given that I have written a number of articles on what has been termed ‘objectum sexuality’ (involving individuals who have sexual relationships with cars, trains, and bicycles) I wouldn’t have been overly surprised to hear of such a story, but the story is a hoax. My suspicions were raised by some of the alleged quotes from the nameless police officers in the story but the real clue to the story being a hoax (along with the follow-up stories) was that these stories were written by a ‘Crime correspondent’ called ‘Hugh Dunnett’ (‘whodunit’).

Despite the story being a hoax I decided to see if there were any real examples of ‘tractor sex’. A quick bit of Googling demonstrated that there is certainly a niche market for pornographic videos featuring individuals having sex in tractors including Porn Hub and elsewhere (please be warned that clicking on these links leads directly to sexually explicit material). I also found the occasional admission in online forums of individuals who had sexual fantasies concerning tractors but these appeared to be nothing more than isolated dreams rather than being a fetish that was enacted. I also discovered that there is a sexual practice colloquially known as a ‘Kentucky Tractor Puller’. According to online sources, the description is as follows:

“The act of a male and a male or male and a female preforming anal sex. During sex the receiver clenches their butt-cheeks tightly and runs with the penis still in the buttocks”.

I then went onto Google Scholar, and a just published 2018 paper appeared after I had typed in the words ‘tractor sex’. A paper in the journal Medical Journal Armed Forces India by Antonio Ventriglio and colleagues entitled ‘Sexuality in the 21st century: Leather or rubber? Fetishism explained’. Unfortunately, I was disappointed by what I found. In the very first paragraph of the paper, the authors repeated the hoax story:

“In the UK, in early October 2015, a man was arrested for having had sex with 450 tractors. According to the news report, he was found to have over 5000 tractor images on his laptop. He had a special desire for John Deere and Massey Ferguson tractors, particularly the green ones. He was into axle grease, which apparently turned him on sexually. He was placed on the Sexual Offenders’ Register”.

Although academics (including myself) can be fooled by hoaxes, the authors of the paper clearly didn’t even check out the original source. In fact, the authors cited the article that appeared in the Daily Star but if they had continued to read the story to the very end, they would have seen the fact that even the newspaper believed the story to be a hoax.

I then found a 2016 paper by Brian Holoyda and William Newman in the International Journal of Law and Psychiatry entitled ‘Childhood animal cruelty, bestiality, and the link to adult interpersonal violence’. I knew the word ‘tractor’ appeared in the paper but I had no idea in what context. I emailed Dr. Holoyda who sent me the paper. I had been expecting to read that there was some kind of bestial act relating to a tractor but this wasn’t the case. It cited a paper published in a 1963 issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry by Dr. John Macdonald which related sadistic acts by a farmer (the so-called ‘homocidal triad‘) towards animals:

“Macdonald described some patients who were “very sadistic,” including one patient who “derived satisfaction from telling his wife again and again of an incident in which he assisted in the birth of a calf by hitching the cow to a post and tying a rope from the presenting legs of the calf to his tractor,” the result being that he “gunned the motor and eviscerated the cow” (p. 126). He claimed that “in the very sadistic patients, the triad of childhood cruelty to animals, fire setting and enuresis was often encountered” (p. 126–127), though he never explicitly stated how many patients had a history of these comorbid behaviors. Macdonald reported that within six months of his study, two patients killed a person, neither of whom he identified as having a history of animal cruelty (or enuresis or fire setting, for that matter), and that one patient with schizophrenia committed suicide”.

I ought to add that bestial acts by farmers is not uncommon. The Kinsey Reports (of 1948 and 1953) arguably shocked its readers when it reported that 8% of males and 4% females had at least one sexual experience with an animal. As with necrophiliacs who are often employed in jobs that provide regular contact with dead people, the Kinsey Reports provided much higher prevalence for zoophilic acts among those who worked on farms (for instance, 17% males who had worked on farms had experienced an orgasmic episode involving animals). A more recent reference by Dr. Anil Aggrawal outlining his new typology for zoophilia (which I overviewed in a previous blog) noted the cases of what he described as opportunistic zoosexuals who have normal sexual encounters but who Aggrawal argued would not refrain from having sexual intercourse with animals if the opportunity arose. Aggrawal claims that such behaviour occurs most often in incarcerated or stranded persons, or when the person sees an opportunity to have sex with an animal when they are sure no-one else is present (e.g., farmhands). Aggrawal claims that opportunistic zoosexuals have no emotional attachment to animals despite having sex with them.

Thankfully, I did manage to locate one paper in the academic literature where tractors were inextricably linked with paraphilic behaviour. In 1993, a paper by P.E. Dietz and R.L. O’Halloran entitled ‘Autoerotic fatalities with power hydraulics’ published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences. They reported two case studies of men who used “the hydraulic shovels on tractors to suspend themselves for masochistic sexual stimulation”. One of the men was an objectophile (although the authors didn’t call him that – I am using Dr. Amy Marsh’s definition in a 2010 paper on objectum sexuality in the Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality to classify him as such). This man actually developed a romantic attachment to his tractor, and went as far as giving his tractor a name and writing poetry about it. Unfortunately, the man “died accidentally while intentionally asphyxiating himself through suspension by the neck, leaving clues that he enjoyed perceptual distortions during asphyxiation”.

The second case was a man who was found dead in a barn lying on his front pinned under the hydraulic shovel of his tractor. His body was covered with semen stains and there was evidence of masochistic sexual bondage. His clothes were folded neatly away nearby. He was found naked except for a pair of women’s red shoes (with 8 inch heels), knee high stockings and tape duct wrapped around his ankles. Ropes led from his feet to the tractor which when raised would lift his inverted body causing complete suspension. It is not known exactly what happened but it is likely that the engine stalled and he was crushed underneath the tractor shovel. He died of positional asphyxiation by chest compression. This was an atypical autoerotic fatality because he did not purposely use asphyxiation but it did cause his death.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Distinguished Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Aggrawal A. (2009). Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects of Sexual Crimes and Unusual Sexual Practices. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Aggrawal, A. (2011). A new classification of zoophilia. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 18, 73-78.

Dietz, P. E., & O’Halloran, R.L. (1993). Autoerotic fatalities with power hydraulics. Journal of Forensic Science, 38(2), 359-364.

“Dunnett, H.” (2015). Suffolk man ‘had sex with 450 tractors’. Suffolk Gazette. Located at: https://www.suffolkgazette.com/news/suffolk-man-sex-with-tractors/

Holoyda, B. J., & Newman, W. J. (2016). Childhood animal cruelty, bestiality, and the link to adult interpersonal violence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 47, 129-135.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C.E., Gebhard, P.H. (1953). Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C.E., (1948). Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company.

Love, B. (2001). Encyclopedia of Unusual Sex Practices. London: Greenwich Editions.

Macdonald, J. M. (1963). The threat to kill. American Journal of Psychiatry, 120(2), 125-130.

Marsh, A. (2010). Love among the objectum sexuals. Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, 13, March 1. Located at: http://www.ejhs.org/volume13/ObjSexuals.htm

Rawle, T. (2015). Perv who romped with 450 TRACTORS caught with 5,000 racy pics of farming vehicles. Daily Star, October 21. Located at: https://www.dailystar.co.uk/news/latest-news/471306/Pervert-tractor-sex-fetish-farm-vehicles-arrested

Ventriglio, A., Bhat, P. S., Torales, J., & Bhugra, D. (2018). Sexuality in the 21st century: Leather or rubber? Fetishism explained. Medical Journal Armed Forces India. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2018.09.009

Date crime: A beginner’s guide to ‘love bombing’

Recently, I did an interview with a journalist about ‘love bombing’ described by her as a new phenomenon occurring in online dating and is “when someone showers you with attention, promising the world but when you respond they go cold and stop responding”. However, there is nothing new about ‘love bombing’ because the term has been around since the 1970s except it has traditionally been described as a practice by religious organisations and cults in relation to the indoctrination of new recruits. According to a number of different sources, the term ‘love bombing’ was coined by the Unification Church of the United States founded by Sun Myung Moon (and why individuals in the cult are often referred to as ‘Moonies’). A number of academics have written about ‘love bombing’ within cult movements. For instance, Thomas Robbins in a 1984 issue of the journal Social Analysis noted that:

“Many elements involved in controversies over alleged cultist brainwashing entail trans-valuational conflicts related to alternative internal vs. external perspectives. The display of affection toward new and potential converts (‘love bombing’), which might be interpreted as a kindness or an idealistic manifestation of devotees’ belief that their relationship to spiritual truth and divine love enables them to radiate love and win others to truth, is also commonly interpreted as a sinister ‘coercive’ technique (Singer, 1977)”.

In a 2002 issue of the journal Human Relations, Dennis Tourish and Ashly Pinnington wrote that the practice of ‘love bombing’ is derived from the interpersonal perception literature and is a form of ‘ingratiation’ (taken from Edward Jones’ 1964 book of the same name). They then cite from Jones’ 1990 book Interpersonal Perception:

“There is little secret or surprise in the contention that we like people who agree with us, who say nice things about us, who seem to possess such positive attributes as warmth, understanding, and compassion, and who would ‘go out of their way’ to do things for us”.

Tourish again (this time with Naheed Vatcha) in a 2005 issue of the journal Leadership noted that cults use ‘love bombing’ as an emotionally draining recruitment strategy and that it is a form of positive reinforcement. More specifically, they noted that:

“Cults make great ceremony of showing individual consideration for their members. One of the most commonly cited cult recruitment techniques is generally known as ‘love bombing’ (Hassan, 1988). Prospective recruits are showered with attention, which expands to affection and then often grows into a plausible simulation of love. This is the courtship phase of the recruitment ritual. The leader wishes to seduce the new recruit into the organization’s embrace, slowly habituating them to its strange rituals and complex belief systems. At this early stage resistance will be at its highest. Individual consideration is a perfect means to overcome it, by blurring the distinctions between personal relationships, theoretical constructs and bizarre behaviors”.

More recently, the practice of ‘love bombing’ has been used in other contexts such by gang leaders or pimps as a way of controlling their victims (as outlined in the 2009 book Gangs and Girls: Understanding Juvenile Prostitution by Michel Dorais and Patrice Corriveau), and within the context of everyday dating and online dating. One article that has been cited a lot in the press relating to the use of ‘love bombing’ in day-to-day relationships is a populist article written for Psychology Today by Dr. Dale Archer. He noted that:

“Notorious cult leaders Jim Jones, Charles Manson, and David Koresh weaponized love bombing, using it to con followers into committing mass suicide and murder. Pimps and gang leaders use love bombing to encourage loyalty and obedience as well”.

Dr. Archer says that ‘love bombing’ works because “humans have a natural need to feel good about who we are, and often we can’t fill this need on our own”. He says that there are times of high susceptibility to being ‘love bombed’ such as losing a job or going through a divorce. Irrespective of why or where the susceptibility has arisen, Archer claims that love bombers “are experts at detecting low self-esteem, and exploiting it”. He then goes on to claim that:

“The paradox of love bombing is that people who use it aren’t always seeking targets that broadcast insecurity for all to see. On the contrary, the love bomber is also insecure, so to boost their ego, the target must at least seem like a great “catch.” Maybe she’s the beautiful woman, who’s lonely because her beauty intimidates people, or he’s the guy with the great career whose wife left him for his best friend, or she’s the hard-nosed businesswoman, who’s avoided marriage and motherhood because her childhood was so traumatic. On paper, these folks are attractive, but something makes them doubt their own value. Along comes the love bomber to shower them with affection and attention. The dopamine rush of the new romance is vastly more powerful than it would be if the target had a healthy self-esteem, because the love bomber fills a need the target can’t fill on her own”.

My own expertise on ‘love bombing’ is limited (to say the least). However, I did attempt to answer the questions I was asked, and here are my verbatim replies.

It seems like [‘love bombing’] quite an addictive and compulsive behaviour – what do you make of it?

There is no evidence that love bombing is either addictive or compulsive and is simply a specific behaviour that although may be repetitive and habitual is not something that would be done compulsively (because the love bombing is planned and focused) or addictively (because love bombing not something that they would do that compromises everything else in their life).

Are there any psychological reasons why people behave like this?

I don’t know of any psychological research that has been done on love bombing but the concept is not new as it has been in the academic literature since the 1970s in relation to indoctrinating individuals into religious cults. Love bombing is a manipulative strategy to make individuals more emotionally pliable. My guess is that in a relationship setting (rather than a cult setting) the individuals engaged in love bombing are likely to be egomaniacs and/or narcissists who like to feel dominant and powerful and/or love psychologically humiliating others.

In my experience, and according to some of the people I’ve interviewed who are guilty of ‘love bombing’ – they do it to multiple people at once.

If love bombing is part of an individual’s behavioural repertoire there is no reason why they wouldn’t do it with more than one person at the same time. However, I don’t know of any research that has shown this to be the case but it wouldn’t surprise me if some individuals were unfaithful love bombers (but I’m sure there are serial love bombers who just do it from one relationship to the next without being physically or emotionally unfaithful).

Is it to straightforward to blame tech for such behaviours – is it just an amplification of behaviours people already exhibit in real life? The temptation always seems to be to blame it on the internet.

The internet tends to facilitate pre-existing problematic behaviour rather than cause it. However, it is well known that the internet is a disinhibiting medium and that individuals lower their psychological guard online. In the case of relationships, the perceived anonymity of being online means that individuals reveal things about themselves, often very private things, because the medium is non-face-to-face, non-threatening, non-alienating and non-stigmatising. Individuals can develop deep emotional relationships online without even having met the other person because of the internet’s disinhibiting properties. Consequently, online methods of communication are another tool in love bomber’s armoury in (initially) showering their professed love for somebody and can happen 24/7 (something which couldn’t have happened in the days prior to online ubiquity).

Where and how, if at all, does this sort of problematic behaviour intersect with sex and love addiction?

I don’t see any overlaps between ‘love bombing’ and sex addiction as they are two completely different constructs and have completely different underlying motivations with little in the way of crossover. Obviously, love bombing could be used as a method to increase the likelihood of sex (because flattery goes a long way). However, if the ultimate goal is psychological control of another person’s emotions, sex is simply a by-product of love bombing rather than the main goal.

Anything else you would like to add?

As far as I can tell, there has never been any empirical research on ‘love bombing’ within the context of dating so all my responses to the questions I was asked are speculative. However, I do think this is an area that would benefit from scientific investigation given how important personal relationships are within our lives. At the very least such research might uncover the signs and strategies that ‘love bombers’ typically use and might prevent a lot of emotional pain felt by individuals not rushing head first (or should that be heart first?) into such relationships in the first place.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Archer, D. (2017). The manipulative partner’s most devious tactic. Psychology Today, March 6. Located at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/reading-between-the-headlines/201703/the-manipulative-partners-most-devious-tactic

Dorais, M. & Corriveau, P. (2009). Gangs and Girls: Understanding Juvenile Prostitution. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press.

Griffiths, M.D. (2000). Cyber affairs – A new area for psychological research. Psychology Review, 7(1), 28-31.

Griffiths, M.D. (2000). Excessive internet use: Implications for sexual behavior. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 3, 537-552.

Griffiths, M.D. (2001). Sex on the internet: Observations and implications for sex addiction. Journal of Sex Research, 38, 333-342.

Griffiths, M.D. (2012). Internet sex addiction: A review of empirical research. Addiction Research and Theory, 20, 111-124.

Hassan, S. (1988) Combating Cult Mind Control. Rochester: Park Press.

James, O. (2012). Love bombing: Reset your child’s emotional thermostat. London: Karnac Books.

Jones, E. (1964). Ingratiation. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts

Jones, E. (1990). Interpersonal Perception. New York: WH Freeman.

Robbins, T. (1984). Constructing cultist “mind control”. Sociological Analysis, 45(3), 241-256

Singer, M. (1977). Therapy with ex-cultists. National Association of Private Psychiatric Hospitals Journal, 9(4), 15-18.

Tourish, D., & Pinnington, A. (2002). Transformational leadership, corporate cultism and the spirituality paradigm: An unholy trinity in the workplace? Human Relations, 55(2), 147-172.

Tourish, D., & Vatcha, N. (2005). Charismatic leadership and corporate cultism at Enron: The elimination of dissent, the promotion of conformity and organizational collapse. Leadership, 1(4), 455-480.

Wikipedia (2017). Love bombing. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Love_bombing

Trip it up and start again: Dark tourism (revisited)

Last week, there were numerous stories in the British press about plans to display the car that Princess Diana was killed in a US museum. Much of this coverage described the plans as ‘sick’ and ‘distasteful’ but is the latest in a very long line of an example of ‘dark tourism’. In a previous blog I briefly examined ‘disaster tourism’, a form of ‘dark tourism’. Since writing that blog I came across an interesting book chapter by the Slovenian researcher Dr. Lea Kuznik entitled ‘Fifty shades of dark stories’ examining the many motivations for engaging in the seedier side of tourism. Dark tourism is something that I have been guilty of myself. For instance, as a Beatles fanatic, when I first went to New York, I went to the Dakota apartments where John Lennon had been shot by Mark David Chapman. In her chapter, Dr. Kuznik notes that:

“Dark tourism is a special type of tourism, which involves visits to tourist attractions and destinations that are associated with death, suffering, disasters and tragedies venues. Visiting dark tourist destinations in the world is the phenomenon of the twenty-first century, but also has a very long heritage. Number of visitors of war areas, scenes of accidents, tragedies, disasters, places connected with ghosts, paranormal activities, witches and witchhunt trials, cursed places, is rising steeply”.

As I noted in my previous blog, the motivations for such behaviour is varied. Those working in the print and broadcast media often live by the maxim that ‘if it bleeds, it leads’ (meaning that death and disaster sell). Clearly whenever anything hits the front of newspapers or is the lead story on radio and television, it gains notoriety and infamy. This applies to bad things as well as good things and is one of the reasons why dark tourism has become so popular. Kuznik notes that although dark tourism has a long history, it has only become a topic for academic study since the mid-1990s. Dr. Kuznik observes that:

“The term dark tourism was coined by Foley and Lennon (1996) to describe the attraction of visitors to tourism sites associated with death, disaster, and depravity. Other notable definitions of dark tourism include the act of travel to sites associated with death, suffering and the seemingly macabre (Stone, 2006), and as visitations to places where tragedies or historically noteworthy death has occurred and that continue to impact our lives (Tarlow, 2005). Scholars have further developed and applied alternative terminology in dealing with such travel and visitation, including thanatourism (Seaton, 1996), black spot tourism (Rojek, 1993), atrocity heritage tourism (Tunbridge & Ashworth, 1996), and morbid tourism (Blom, 2000). In a context similar to ‘dark tourism’, terms like ‘macabre tourism’, ‘tourism of mourning’ and ‘dark heritage tourism’ are also in use. Among these terms, dark tourism remains the most widely applied in academic research (Sharpley, 2009)”.

Kuznik also notes that dark tourism has been referred to as “place-specific tourism”. Consequently, some researchers began to classify dark tourism sites based upon their defining characteristics. As Kuznik notes:

“Miles (2002) proposed a darker-lighter tourism paradigm in which there remains a distinction between dark and darker tourism according to the greater or lesser extent of the macabre and the morose. In this way, the sites of the holocaust, for example, can be divided into dark and darker tourism when it comes to their authenticity and scope of interpretation…On the basis of the dark tourism paradigm of Miles (2002), Stone (2006) proposed a spectrum of dark tourism supply which classifies sites according to their perceived features, and from these, the degree or shade of darkness (darkest to lightest) with which they can be characterised. This spectrum has seven types of dark tourism suppliers, ranging from Dark Fun Factories as the lightest, to Dark Camps of Genocide as the darkest. A specific example of the lightest suppliers would be dungeon attractions, such as London Dungeon, or planned ventures such as Dracula Park in Romania. In contrast, examples of the darkest sites include genocide sites in Rwanda, Cambodia, or Kosovo, as well as holocaust sites such as Auschwitz-Birkenau”.

In relation to the reasons for visiting dark tourism sites, Kuznik came up with seven main motivations for why we as humans seek out such experiences (i.e., curiosity, education, survivor guilt, remembrance, nostalgia, empathy, and horror) that are outlined below (please note that the descriptions are edited verbatim from Kuznik’s chapter)

- Curiosity: “Many tourists are interested in the unusual and the unique, whether this be a natural phenomenon (e.g. Niagara Falls), an artistic or historical structure (e.g. the pyramids in Egypt), or spectacular events (e.g. a royal wedding). Importantly, the reasons why tourists are attracted to dark tourism sites derive, at least in part, from the same curiosity which motivates a visit to Niagara Falls. Visiting dark tourism sites is an out of the ordinary experience, and thus attractive for its uniqueness and as a means of satisfying human curiosity. So the main reason is the experience of the unusual”.

- Empathy: “One of the reasons for visiting dark tourism sites may be empathy, which is an acceptable way of expressing a fascination with horror…In many respects, the interpretation of dark tourism sites can be difficult and sensitive, given the message of the site as forwarded by exhibition curators can at times conflict with the understandings of visitors”.

- Horror: “Horror is regarded as one of the key reasons for visiting dark tourism sites, and in particular, sites of atrocity…Relating atrocity as heritage at a site is thus as entertaining as any media depiction of a story, and for precisely the same reasons and with the same moral overtones. Such tourism products or examples are: Ghost Walks around sites of execution or murder (Ghost Tour of Prague), Murder Trails found in many cities like Jack the Ripper in London”.

- Education: “In much tourism literature it has been claimed that one of the main motivations for travel is the gaining of knowledge, and the quest for authentic experiences. One of the core missions of cultural and heritage tourism in particular is to provide educational opportunities to visitors through guided tours and interpretation. Similarly, individual visits to dark tourism sites to gain knowledge, understanding, and educational opportunities, continue to have intrinsic educational value…many dark tourism attractions or sites are considered important destinations for school educational field trips, achieving education through experiential learning”.

- Nostalgia: “Nostalgia can be broadly described as yearning for the past…or as a wistful mood that an object, a scene, a smell or a strain of music evokes…In this respect Smith (1996) examined war tourism sites and concluded that old soldiers do go back to the battlefields, to revisit and remember the days of their youth”.

- Remembrance: “Remembrance is a vital human activity connecting us to our past…Remembrance helps people formulate an identity, allowing them to learn from past mistakes, and to go forward with a clear vision of the future. In the context of dark tourism, remembrance and memory are considered key elements in the importance of sites”.

- Survivor’s guilt: “One of the distinctive characteristics of dark tourism is the type of visitors such sites attract, which include survivors and victim‘s families returning to the scene of death or disaster. These types of visitors are particularly prevalent at sites associated with Second World War and the holocaust. For many survivors returning to the scene of death and atrocity can achieve a therapeutic effect by resolving grief, and can build understanding of how terrible things came to have happened. This can be very emotional experience”.

Dr. Kuznik also developed a new typology of “dark places in nature”. The typology comprised 17 types of dark places and are briefly outlined below.

- Disaster area tourism: Visiting places of natural disaster after hurricanes, tsunamis, volcanic destructions, etc.

- Grave tourism: Visiting famous cemeteries, or graves and mausoleums of famous individuals.

- War or battlefield tourism: Visiting places where wars and battles took place.

- Holocaust tourism: Visiting Nazi concentration camps, memorial sites, memorial museums, etc.

- Genocide tourism: Visiting places where genocide took place such as the killing fields in Cambodia.

- Prison tourism: Visiting former prisons such as Alcatraz.

- Communism tourism: Visiting places like North Korea.

- Cold war and iron curtain tourism: Visiting places and remains associated with the cold war such as the Berlin Wall.

- Nuclear tourism: Visiting sites where nuclear disasters took place (e.g. Chernobyl in the Ukraine) or where nuclear bombs were exploded (e.g., Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan).

- Murderers and murderous places tourism: Visiting sites where killers and serial killers murdered their victims (‘Jack the Ripper’ walks in London, where Lee Harvey Oswald killed J.F. Kennedy in Dallas)

- Slum tourism: Visiting impoverished and slum areas in countries such as India and Brazil, Kenya.

- Terrorist tourism: Visiting places such Ground Zero (where the Twin Towers used to be) in New York City

- Paranormal tourism: Visiting crop circle sites, places where UFO sightings took place, haunted houses (e.g., Amityville), etc.

- Witched tourism: Visiting towns or cities where witches congregated (e.g., Salem in Massachusetts).

- Accident tourism: Visiting places where infamous accidents took place (e.g. the Paris tunnel where Princess Diana died in a car accident).

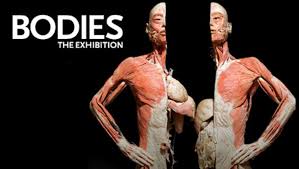

- Icky medical tourism: Visiting medical museums and body exhibitions.

- Dark amusement tourism: Visiting themed walks and amusement parks that are based on ghosts and horror figures (e.g., Dracula).

Looking at these different types quickly I reached the conclusion that I would class myself as a ‘dark tourist’ as I have engaged in many of these and no doubt reflects my own interest in the more extreme aspects of the lived human experience.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Ashworth, G., & Hartmann, R. (2005). Introduction: managing atrocity for tourism. In G. Ashworth & R. Hartmann (Eds.), Horror and human tragedy revisited: the management of sites of atrocities for tourism (pp. 1–14). Sydney: Cognizant Communication Corporation.

Blom, T. (2000). Morbid tourism – a postmodern market niche with an example from Althorp. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 54(1), 29–36.

Dann, G. M., & Seaton, A. V. (2001). Slavery, contested heritage and thanatourism. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 2(3-4), 1-29.

Foley, M., & Lennon, J. (1996). JFK and dark tourism: A fascination with assassination. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 198–211.

Foley, M., & Lennon, J. (2000). Dark tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(1), 68-78.

Kuznik, L. (2018). Fifty shades of dark stories. In Mehdi Khosrow-Pour, D.B.A. (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology (Fourth Edition). (pp.4077-4087). Pennsylvania: IGI Global.

Miles, W.F. (2002). Auschwitz: Museum interpretation and darker tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(4), 1175-1178.

Podoshen, J. S. (2013). Dark tourism motivations: Simulation, emotional contagion and topographic comparison. Tourism Management, 35, 263-271.

Rojek, C. (1993). Ways of escape. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Seaton, A. V. (1996). From thanatopsis to thanatourism: Guided by the dark. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 234–244.

Sharpley, R., & Stone, P. R. (Eds.). (2009). The darker side of travel: the theory and practice of dark tourism. Bristol: Channel View.

Smith, V. L. (1996). War and its tourist attractions. In A. Pizam & Y. Mansfeld (Eds.), Tourism, crime and international security issues (pp. 247–264). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Stone, P. R. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. Tourism, 54(2), 145–160.

Strange, C., & Kempa, M. (2003). Shades of dark tourism: Alcatraz and Robben Island. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(2), 386-405.

Tarlow, P.E. (2005). Dark tourism: the appealing dark side of tourism and more. In M. Novelli (Ed.), Niche tourism – Contemporary issues, trends and cases (pp. 47–58). Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Tunbridge, J.E., & Ashworth, G. (1996). Dissonant heritage: The management of the past as a resource in conflict. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Serial delights: Killing as an addiction

A couple of days ago I watched the 2007 US psychological thriller Mr. Brooks. The film is about a celebrated businessman (Mr. Earl Brooks played by Kevin Costner) who also happens to be serial killer (known as the ‘thumbprint killer’). The reason I mention all this is that the explanation given in the film by Earl for the serial killing is that it was an addiction. A number of times in the film he is seem attending Alcoholics Anonymous and quoting from the 12-step recovery program to help him ‘beat his addiction’. With the help of the AA Fellowship, he had managed not to kill anyone for two years but at the start of the film, Earl’s psychological alter-ego (‘Marshall’ played by William Hurt) manages to coerce Earl into killing once again. I won’t spoil the plot for people who have not seen the film but the underlying theme that serial killing is an addiction that Earl is constantly fighting against, is embedded in an implicit narrative that addiction somehow ‘explains’ his behaviour and that he is not really responsible for it. This is not a view I hold myself as all addicts have to take some responsibility for their behaviour.

The idea of serial killing being conceptualized as an addiction in popular culture is not new. For instance, Brian Masters book about British serial killer Dennis Nilsen (who killed at least 12 young men and was also a necrophile) was entitled Killing for Company: The Story of a Man Addicted to Murder, and Mikaela Sitford’s book about Harold Shipman, the British GP (aka ‘Dr. Death’) who killed over 200 people, was entitled Addicted to Murder: The True Story of Dr. Harold Shipman.

One of the things that I have always argued throughout my career, is that someone cannot become addicted to an activity or a substance unless they are constantly being rewarded (either by continual positive and/or negative reinforcement). Given that serial killing is a discontinuous activity (i.e., it happens relatively infrequently rather than every hour or day) how could killing be an addiction? One answer is that the act of killing is part of the wider behaviour in that the preoccupation with killing can also include the re-enacting of past kills and the keeping of ‘trophies’ from the victims (which I overviewed in a previous blog). As the author of the book Freud, Profiled: Serial Killer noted:

“The serial killer is most often described as a kind of addict. Murder is his addiction, the thrill achieved in murder his ‘kick.’ This addiction requires a maintenance ‘fix.’ At first, the experience is wonderfully exhilarating, later the fix is needed to just feel normal again. It is a hard habit to break, the hungering sensation to consume another life returns. Between murders, they often play back video or sound recordings or look at photos made of their previous murders. This voyeurism provides a surrogate death-meal until their next feeding”.

In Eric Hickey’s 2010 book Serial Murderers and Their Victims, Dr. Hickey makes reference to an unpublished 1990 monograph by Dr. Victor Cline who outlined a four-factor addiction syndrome in relation to sexual serial killers who (so-called ‘lust murderers’ that I also examined in a previous blog). More specifically:

“The offender first experiences ‘addiction’ similar to the physiological/psychological addiction to drugs, which then generates stress in his or her everyday activities. The person then enters a stage of ‘escalation’, in which the appetite for more deviant, bizarre, and explicit sexual material is fostered. Third, the person gradually becomes ‘desensitized’ to that which was once revolting and taboo-breaking. Finally, the person begins to ‘act out’ the things that he or she has seen”.

This four-stage model is arguably applicable to serial killing more generally. It also appears to be backed up by one of the most notorious serial killers, Ted Bundy. In an interview with psychologist Dr. James Dobson (found in Harold Schecter’s 2003 book The Serial Killer Files: The Who, What, Where, How, and Why of the World’s Most Terrifying Murderers), Bundy claimed:

“Once you become addicted to [pornography], and I look at this as a kind of addiction, you look for more potent, more explicit, more graphic kinds of material. Like an addiction, you keep craving something which is harder and gives you a greater sense of excitement, until you reach the point where the pornography only goes so far – that jumping-off point where you begin to think maybe actually doing it will give you that which is just beyond reading about it and looking at it”.

Dr. Hickey claims that such urges to kill are fuelled by fantasies that have become well-developed and killers to vicariously gain control of other individual. He also believes that fantasies for lust killers are far greater than an escape, and becomes the focal point of all behaviour. He concludes by saying that “even though the killer is able to maintain contact with reality, the world of fantasy becomes as addictive as an escape into drugs”. In the book The Serial Killer Files, Harold Schechter notes that:

“For homicidal psychopaths, lust-killing often becomes an addiction. Like heroin users, they not only become dependent on the thrilling sensation – the rush – of torture, rape, and murder; they come to require ever greater and more frequent fixes. After a while, merely stabbing a co-ed to death every few months isn’t enough. They have to kill every few weeks, then every few days. And to achieve the highest pitch of arousal, they have to torture the victim before putting her to death. This kind of escalation can easily lead to the killer’s own destruction. Like a junkie who ODs in his urgent quest to satisfy his cravings, serial killers are often undone by their increasingly unbridled sadism, which drives them to such reckless extremes that they are finally caught. Monsters tend to be sadists, deriving sexual gratification from imposing pain on others. Their secret perversions, at first sporadic, often trap them in a pattern as the intervals between indulgences become briefer: it is a pattern whose repetitions develop into a hysterical crescendo, as if from one outrage to another the monster were seeking as a climax his own annihilation”.

Schecter uses the ‘addiction’ explanation for serial killing throughout his writings even for serial killers from the past including American nurse Jane Toppan (the ‘Angel of Death’) who confessed to 33 murders in 1901 and died in 1938 (“she became addicted to murder”), cannibalistic child serial killers Gilles Garnier (died in 1573) and Peter Stubbe (died 1589) (“both became addicted to murder and cannibalism, both preferred to prey upon children”), and Lydia Sherman (died 1878) who killed 8 children including six of her own (“confirmed predator, addicted to cruelty and death”).

In a recent 2012 paper on mental disorders in serial killers in the Iranian Journal of Medical Law, Dr. N. Mehra and A.S. Pirouz quoted the literary academic Akira Lippit who argued that in films, the “completion of each serial murder lays the foundation for the next act which in turn precipitates future acts, leaving the serial subject always wanting more, always hungry, addicted”. They then go on to conclude that:

“Once a killer has tasted the success of a kill, and is not apprehended, it will ultimately mean he will strike again. He put it simply, that once something good has happened, something that made the killer feel good, and powerful, and then they will not hesitate to try it again. The first attempt may leave them with a feeling of fear but at the same time, it is like an addictive drug. Some killers revisit the crime scene or take trophies, such as jewelry or body parts, or video tape the scenario so as to be able to re-live the actual feeling of power at a later date”.

Although I haven’t done an extensive review of the literature, I do think it’s possible – even on the slimmest of empirical bases presented here – to conceptualize serial killing as a potential behavioural addiction for some individuals. However, it will always depend upon how addiction is defined in the first place.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Aggrawal A. (2009). Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects of Sexual Crimes and Unusual Sexual Practices. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Brophy, J. (1967). The Meaning of Murder. London: Crowell.

Hickey, E.W. (2010). Serial Murderers and Their Victims (Fifth Edition). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Lippit, A.M. (1996). The infinite series: Fathers, cannibals, chemists. Criticism, Summer, 1-18.

Masters, B. (1986). Killing for Company: The Story of a Man Addicted to Murder. New York: Stein and Day.

Mehra, N., & Pirouz, A. S. (2012). A study on mental disorder in serial killers. Iranian Journal of Medical Law, 1(1), 38-51.

Miller, E. (2014). Freud, Profiled: Serial Killer. San Diego: New Directions Publishing.

Schecter, H. (2003). The Serial Killer Files: The Who, What, Where, How, and Why of the World’s Most Terrifying Murderers. New York: Ballantine Books

Sitford, M. (2000). Addicted to Murder: The True Story of Dr. Harold Shipman. London: Virgin Publishing.

Taylor, T. (2014). Is serial killing an addiction? IOL, April 9. Located at: http://www.iol.co.za/news/crime-courts/is-serial-killing-an-addiction-1673542

Art in the right place: Cosey Fanni Tutti’s ‘Art Sex Music’

Five years ago I wrote a blog about one of my favourite bands, Throbbing Gristle (TG; Yorkshire slang for a penile erection). In that article, I noted that TG were arguably one of “the most extreme bands of all time” and “highly confrontational”. They were also the pioneers of ‘industrial music’ and in terms of their ‘songs’, no topic was seen as taboo or off-limits. In short, they explored the dark and obsessive side of the human condition. Their ‘music’ featured highly provocative and disturbing imagery including hard-core pornography, sexual manipulation, school bullying, ultra-violence, sado-masochism, masturbation, ejaculation, castration, cannibalism, Nazism, burns victims, suicide, and serial killers (Myra Hindley and Ian Brady).

I mention all this because I have just spent the last few days reading the autobiography (‘Art Sex Music‘) of Cosey Fanni Tutti (born Christine Newbie), one of the four founding members of TG. It was a fascinating (and in places a harrowing) read. As someone who is a record-collecting completist and having amassed almost everything that TG ever recorded, I found Cosey’s book gripping and read the last 350 pages (out of 500) in a single eight-hour sitting into the small hours of Sunday morning earlier today.

TG grew out of the ‘performance art’ group COUM Transmissions in the mid-1970s comprising Genesis P-Orridge (‘Gen’, born Neil Megson in 1950) and Cosey. At the time, Cosey and Gen were a ‘couple’ (although after reading Cosey’s book, it was an unconventional relationship to say the least). TG officially formed in 1975 when Chris Carter (born 1953) and Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson (1955-2010). Conservative MP Sir Nicholas Fairburn famously called the group “wreckers of civilisation” (which eventually became the title of their 1999 biography by Simon Ford).

As I noted in my previous article, TG are – psychologically – one of the most interesting groups I have ever come across and Cosey’s book pulled no punches. To some extent, Cosey’s book attempted to put the record straight in response to Simon Ford’s book which was arguably a more Gen-oriented account of TG. Anyone reading Cosey’s book will know within a few pages who she sees as the villain of the TG story. Gen is portrayed as an egomaniacal tyrant who manipulated her. Furthermore, she was psychologically and physically abused by Gen throughout their long relationship in the 1970s. Thankfully, Cosey fell in love with fellow band member Chris Carter and he is still the “heartbeat” of the relationship and to who her book is dedicated.

Like many of my favourite groups (The Beatles, The Smiths, The Velvet Underground, Depeche Mode), TG were (in Gestaltian terms) more than the sum of their parts and all four members were critical in them becoming a cult phenomenon. The story of their break up in the early 1980s and their reformation years later had many parallels with that of the Velvet Underground’s split and reformation – particularly the similarities between Gen and Lou Reed who both believed they were leaders of “their” band and who both walked out during their second incarnations.

Cosey is clearly a woman of many talents and after reading her book I would describe her as an artist (and not just a ‘performance artist’), musician (or maybe ‘anti-musician in the Brian Eno sense of the word), writer, and lecturer, as well as former pornographic actress, model, and stripper. It is perhaps her vivid descriptions of her life in the porn industry and as a stripper that (in addition to her accounts of physical and psychological abuse by Gen) were the most difficult to read. For someone as intelligent as Cosey (after leaving school with few academic qualifications but eventually gaining a first-class degree via the Open University), I wasn’t overly convinced by her arguments that her time working in the porn industry both as a model and actress was little more than an art project that she engaged in on her own terms. But that was Cosey’s justification and I have no right to challenge her on it.

What I found even more interesting was how she little connection between her ‘pornographic’ acting and modelling work and her time as a stripper (the latter she did purely for money and to help make ends meet during the 1980s). Her work as a porn model and actress was covert, private, seemingly enjoyable, and done behind closed doors without knowing who the paying end-users were seeing her naked. Her work as a stripper was overt, public, not so enjoyable, and played out on stage directly in front of those paying to see her naked. Two very different types of work and two very different psychologies (at least in the way that Cosey described it).

Obviously both jobs involved getting naked but for Cosey, that appeared to be the only similarity. She never ever had sex for money with any of the clientele that paid to see her strip yet she willingly made money for sex within the porn industry. For Cosey, there was a moral sexual code that she worked within, and that sex as a stripper was a complete no-no. The relationship with Gen was (as I said above) ‘unconventional’ and Gen often urged her and wanted her to have sex with other men (and although she never mentioned it in her book, I could speculate that Gen had some kind of ‘cuckold fetish’ that I examined in a previous blog as well as some kind of voyeur). There were a number of times in the book when Cosey appeared to see herself as some kind of magnet for unwanted attention (particularly exhibitionists – so-called ‘flashers’ – who would non-consensually expose their genitalia in front of Cosey from a young age through to adulthood). Other parts of the book describe emotionally painful experiences (and not just those caused by Gen) including both her parents disowning her and a heartfelt account of a miscarriage (and the hospital that kept her foetus without her knowledge or consent). There are other sections in the book that some readers may find troubling including her menstruation art projects (something that I perhaps should have mentioned in my blog on artists who use their bodily fluids for artistic purposes).

Cosey’s book is a real ‘warts and all’ account of her life including her many health problems, many of which surprisingly matched my own (arrhythmic heart condition, herniated spinal discs, repeated breaking of feet across the lifespan). Another unexpected connection was that her son with Chris Carter (Nick) studied (and almost died of peritonitis) as an undergraduate studying at art at Nottingham University or Nottingham Trent University. I say ‘or’ because at one stage in the book it says that Nick studied at Nottingham University and in another extract it says they were proud parents attending his final degree art show at Nottingham Trent University. I hope it was the latter.

Anyone reading the book would be interested in many of the psychological topics that make an appearance in the book including alcoholism, depression, claustrophobia, egomania, and suicide to name just a few. In previous blogs I’ve looked at whether celebrities are more prone to some psychological conditions including addictions and egomania and the book provides some interesting case study evidence. As a psychologist and a TG fan I loved reading the book.

Dr Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addictions, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Cooper, D. (2012). Sypha presents … Music from the Death Factory: A Throbbing Gristle primer. Located at: http://denniscooper-theweaklings.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/sypha-presents-music-from-death-factory.html?zx=c19a3a826c3170a7

Fanni Tutti, C. (2017). Art Sex Music. Faber & Faber: London.

Ford, S. (1999). Wreckers of Civilization: The Story of Coum Transmissions and Throbbing Gristle. London: Black Dog Publishing.

Kirby, D. (2011). Transgressive representations: Satanic ritual abuse, Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, and First Transmission. Literature and Aesthetics, 21, 134-149.

Kromhout, M. (2007). ‘The Impossible Real Transpires’ – The Concept of Noise in the Twentieth Century: a Kittlerian Analysis. Located at: http://www.mellekromhout.nl/wp-content/uploads/The-Impossible-Real-Transpires.pdf

Reynolds, S. (2006). Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk, 1978–1984. New York: Penguin.

Sarig, R. (1998). The Secret History of Rock: The Most Influential Bands You’ve Never Heard Of. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications.

Walker, J.A. (2009). Cosey Fanni Tutti & Genesis P-Orridge in 1976: Media frenzy, Prostitution-style, Art Design Café, August 10. Located at: http://www.artdesigncafe.com/cosey-fanni-tutti-genesis-p-orridge-1-2009

Wells, S. (2007). A Throbbing Gristle primer. The Guardian, May 27. Located at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2007/may/29/athrobbinggristleprimer

To pee or not to pee? Another look at paraphilic behaviours

Strange, bizarre and unusual human sexual behaviour is a topic that fascinates many people (including myself of course). Last week I got a fair bit of international media coverage being interviewed about the allegations that Donald Trump hired women to perform ‘golden showers’ in front of him (i.e., watching someone urinate for sexual pleasure, typically referred to as urophilia). I was interviewed by the Daily Mirror (and many stories used my quotes in this particular story for other stories elsewhere). I was also commissioned to write an article on the topic for the International Business Times (and on which this blog is primarily based). The IBT wanted me to write an article on whether having a liking for strange and/or bizarre sexual preferences makes that individual more generally deviant.

Although the general public may view many of these behaviours as sexual perversions, those of us that study these behaviours prefer to call them paraphilias (from the Greek “beyond usual or typical love”). Regular readers of my blog will know I’ve written hundreds of articles on this topic. For those of you who have no idea what parahilias really are, they are uncommon types of sexual expression that may appear bizarre and/or socially unacceptable, and represent the extreme end of the sexual continuum. They are typically accompanied by intense sexual arousal to unconventional or non-sexual stimuli. Most adults are aware of paraphilic behaviour where individuals derive sexual pleasure and arousal from sex with children (paedophilia), the giving and/or receiving of pain (sadomasochism), dressing in the clothes of the opposite sex (transvestism), sex with animals (zoophilia), and sex with dead people (necrophilia).

However, there are literally hundreds of paraphilias that are not so well known or researched including sexual arousal from amputees (acrotomophilia), the desire to be an amputee (apotemnophilia), flatulence (eproctophilia), rubbing one’s genitals against another person without their consent (frotteurism), urine (urophilia), faeces (coprophilia), pretending to be a baby (infantilism), tight spaces (claustrophilia), restricted oxygen supply (hypoxyphilia), trees (dendrophilia), vomit (emetophilia), enemas (klismaphilia), sleep (somnophilia), statues (agalmatophilia), and food (sitophilia). [I’ve covered all of these (and more) in my blog so just click on the hyperlinks of you want to know more about the ones I’ve mentioned in this paragraph].

It is thought that paraphilias are rare and affect only a very small percentage of adults. It has been difficult for researchers to estimate the proportion of the population that experience unusual sexual behaviours because much of the scientific literature is based on case studies. However, there is general agreement among the psychiatric community that almost all paraphilias are male dominated (with at least 90% of all those affected being men).

One of the most asked questions in this field is the extent to which engaging in unusual sex acts is deviant? Psychologists and psychiatrists differentiate between paraphilias and paraphilic disorders. Most individuals with paraphilic interests are normal people with absolutely no mental health issues whatsoever. I personally believe that there is nothing wrong with any paraphilic act involving non-normative sex between two or more consenting adults. Those with paraphilic disorders are individuals where their sexual preferences cause the person distress or whose sexual behaviour results in personal harm, or risk of harm, to others. In short, unusual sexual behaviour by itself does not necessarily justify or require treatment.

The element of coercion is another key distinguishing characteristic of paraphilias. Some paraphilias (e.g., sadism, masochism, fetishism, hypoxyphilia, urophilia, coprophilia, klismaphilia) are engaged in alone, or include consensual adults who participate in, observe, or tolerate the particular paraphilic behaviour. These atypical non-coercive behaviours are considered by many psychiatrists to be relatively benign or harmless because there is no violation of anyone’s rights. Atypical coercive paraphilic behaviours are considered much more serious and almost always require treatment (e.g., paedophilia, exhibitionism [exposing one’s genitals to another person without their consent], frotteurism, necrophilia, zoophilia).

For me, informed consent between two or more adults is also critical and is where I draw the line between acceptable and unacceptable. This is why I would class sexual acts with children, animals, and dead people as morally and legally unacceptable. However, I would also class consensual sexual acts between adults that involve criminal activity as unacceptable. For instance, Armin Meiwes, the so-called ‘Rotenburg Cannibal’ gained worldwide notoriety for killing and eating a fellow German male victim (Bernd Jürgen Brande). Brande’s ultimate sexual desire was to be eaten (known as vorarephilia). Here was a case of a highly unusual sexual behaviour where there were two consenting adults but involved the killing of one human being by another.

Because paraphilias typically offer pleasure, many individuals affected do not seek psychological or psychiatric treatment as they live happily with their sexual preference. In short, there is little scientific evidence that unusual sexual behaviour makes you more deviant generally.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Abel, G. G., Becker, J. V., Cunningham-Rathner, J., Mittelman, M., & Rouleau, J. L. (1988). Multiple paraphilic diagnoses among sex offenders. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 16, 153-168.

Buhrich, N. (1983). The association of erotic piercing with homosexuality, sadomasochism, bondage, fetishism, and tattoos. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 12, 167-171.

Collacott, R.A. & Cooper, S.A. (1995). Urine fetish in a man with learning disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 39, 145-147.

Couture, L.A. (2000). Forced retention of bodily waste: The most overlooked form of child maltreatment. Located at: http://www.nospank.net/couture2.htm

Denson, R. (1982). Undinism: The fetishizaton of urine. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 27, 336–338.

Greenhill, R. & Griffiths, M.D. (2015). Compassion, dominance/submission, and curled lips: A thematic analysis of dacryphilic experience. International Journal of Sexual Health, 27, 337-350.

Greenhill, R. & Griffiths, M.D. (2016). Sexual interest as performance, intellect and pathological dilemma: A critical discursive case study of dacryphilia. Psychology and Sexuality, 7, 265-278.

Griffiths, M.D. (2013). Eproctophilia in a young adult male: A case study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1383-1386.

Griffiths, M.D. (2012). The use of online methodologies in studying paraphilias: A review. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1, 143-150.

Griffiths, M.D. (2013). Bizarre sex. New Turn Magazine, 3, 49-51.

Massion-verniory, L. & Dumont, E. (1958). Four cases of undinism. Acta Neurol Psychiatr Belg. 58, 446-59.

Money, J. (1980). Love and Love Sickness: The Science of Sex, Gender Difference and Pair-bonding, John Hopkins University Press.

Mundinger-Klow, G. (2009). The Golden Fetish: Case Histories in the Wild World of Watersports. Paris: Olympia Press.

Skinner, L. J., & Becker, J. V. (1985). Sexual dysfunctions and deviations. In M. Hersen & S. M. Turner (Eds.), Diagnostic interviewing (pp. 211–239). New York: Plenum Press.

Spengler, A. (1977). Manifest sadomasochism of males: Results of an empirical study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 6, 441–456.

The six components comprising selfitis in our new psychometric tool (the Selfitis Behavior Scale [SBS]) were correctly reported but at no point in our paper did we ever say that ‘selfitis’ was a behavioural addiction. What we did write was that (a) “selfitis is a new construct in which future researchers may investigate further in relation to selfitis addiction and/or compulsion” (p.8), and (ii) “the qualitative focus group data from participants strongly implied the presence of ‘selfie addiction’ although the SBS does not specifically assess selfie addiction” (p.11). They also noted that our published paper on selfitis:

The six components comprising selfitis in our new psychometric tool (the Selfitis Behavior Scale [SBS]) were correctly reported but at no point in our paper did we ever say that ‘selfitis’ was a behavioural addiction. What we did write was that (a) “selfitis is a new construct in which future researchers may investigate further in relation to selfitis addiction and/or compulsion” (p.8), and (ii) “the qualitative focus group data from participants strongly implied the presence of ‘selfie addiction’ although the SBS does not specifically assess selfie addiction” (p.11). They also noted that our published paper on selfitis: