Category Archives: Case Studies

Spinal rap: A brief look at my surgical recovery (so far) – Part 2

I was taken to the operating theatre at about 8.30am. My surgery lasted about three hours and at about midday I woke up in the recovery room. The nurse asked me if I felt OK and after realising my surgery was over, I told her I was OK. I then realised I could speak. I could also wiggle my fingers and toes so I also knew I wasn’t paralysed. My very first thought was “If I can talk and I can type, I still have a job”. Within an hour I had drunk water and ate a sandwich and could do both without difficulty or being in pain. However, it became very clear very quickly that I wasn’t in full control of my own hands as well as being unable to walk at all (my right leg could do very little – wiggling my toes was about the limit of my movement). I was also catheterised for the first time in my life.

After eight hours in the recovery room (I should have only been there 1-2 hours but there were no ward beds available) I was moved into a ward just after 8pm with some very serious cases (mostly with individuals who had gone through major brain surgery). All of us on the ward had to have our ‘obs’ (observations – blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, blood sugar, etc.) taken hourly right through the night (so I got no sleep at all). I also had horrendous spasms in both my legs (over 1000 a night for the first week). I was put onto a drug called Baclofen (which I’m still on now).

The day after my operation was not the best. Because of COVID-19 no patients could have visitors. I briefly spoke to my partner on the phone. That was the day’s only highlight. I realised that I couldn’t do basic things with my hands like eat with a knife and fork or hold a pen. The latter really upset me. I keep a very detailed hand-written diary so not being able to write in it was very upsetting for me. I was also unable to give myself a wash so for the next few days I was given a daily body wash by the hospital staff. I couldn’t even hold a toothbrush properly to brush my teeth. I found the whole experience demoralising and degrading. Not being able to shower was horrible. Anyone who knows me will tell you how important showering is to me and my mental health. I shower a minimum twice a day. Not being able to shower felt like an abuse of my human rights. I never felt clean after a body wash. On the day after my operation, it became clear I wouldn’t be going home that day and it soon became apparent that I would be in hospital at least a week.

After a few days, some of my hand functionality began to return. I could just about use a knife and fork and I could pick up a flannel to wash my own face. However, holding a pen and writing with a pen was impossible. Unlike the other patients on the ward (a couple of who were sedated almost 24 hours a day), once I had awoken, I spent the whole day out of bed sat in a chair. I had my iPod so listened to a lot of music but did little else. Couldn’t hold a book or magazine long enough with my hands to read.

On Tuesday (April 20) I had my catheter removed. That seemed like a huge step forward. My partner also dropped my laptop off. I was unable to see her but at least it meant I could Skype her and my children. I also realised that typing was something I could so with my hands relatively easily. Writing a few emails was also good therapy for my fingers and I had a link to the outside world (I don’t have a smartphone, gave up using one in 2019). The hospital physiotherapists had given me hand and leg exercises to do and I spent a lot of time using the ward rotunda as a mini-gym. No-one else was capable of using it (as they were all confined to bed) so I had it 24/7. I was moved to another ward which I was told was “good news” as it meant I needed less specialist care. On Wednesday (April 21) I begged the doctor to allow me to shower. He said I could have one as long as I didn’t get my post-surgery dressing wet. Had to shower in a wheelchair (surreal to say the least) but despite this, it was heavenly to wash my hair and feel clean after six days of humiliating body washes. My dressing was drenched but I didn’t care. I felt clean and alive. I felt co-operative and communicative.

Just after the shower, I had an unexpected visitor. A doctor visited me and told me that I would be leaving Queen’s Medical Centre and would be moving to another hospital (City Hospital) to a specialist rehabilitation unit (Linden Lodge). She said she would try to get me a bed there for that weekend and that I would probably be there for 4-6 weeks. My emotions were mixed. I was glad to be moving to a place with dedicated and specialist care, but was surprised to hear that I would be in hospital for another 4-6 weeks.

At lunchtime that day, I got the unexpected news that there was a bed at Linden Lodge that evening and I was told to pack up all my stuff (not that I had much to pack). At 7pm I was transported by ambulance (first time I had ever been in one) over to my new temporary home. I was given my own room (which was great) and I unpacked the few things I had. My partner had dropped off clothes at the unit but again I was unable to see her due to the COVID-19 visiting restrictions. At one point in the evening, I decided to sit on the floor rather than the bed to get undressed for bed (I found it easier than being on the bed). When the nurse came in and found me sitting on the floor, she thought I had fallen (I hadn’t) but recorded in her notes that I had fallen.

On the Thursday morning (April 22, one week after my operation) I began life in Linden Lodge. I wasn’t allowed to shower until I had been “assessed” by an occupational therapist. I finally managed to have an unsupervised shower (in a wheelchair) early afternoon even though I was not “assessed”. I also moved room nearer the nursing staff because I was deemed as someone who needed to be watched more closely because they thought I had fallen on the floor the first night I was in here. The more I protested the less they believed me. It was even written up outside my room that I was susceptible to falls (which was true prior to my operation but not something I had done in hospital).

Since then, things have gone slowly. I was told after my initial assessments that I would likely be here for three months (i.e., until August). However, I left hospital on June 22 (after 67 days in hospital). The hardest thing I had to deal with was (until about 40 days into my stay) the ‘no visitors’ policy. I did see my partner a couple of times outside the unit through the iron bars (which felt a bit like being in prison). Over the past 12 weeks, a lot of my hand functionality has returned although I still have some difficulties. There are things that I now consider easy (typing, eating with a knife and fork, sponging myself in the shower), some that I can do but have to focus (writing with a pen, putting socks on, washing my hair, brushing my teeth, doing a crossword), and some things which are very difficult but I can do (e.g., shaving, tying shoelaces).

The first Sunday I was in the unit, I found a sentence that had all letters of the alphabet (“Pack my box with five dozen liquor jugs”) and spent hours trying to write it out in upper and lower case letters with a pen. Very difficult and very time consuming (but I did it). Over the next few weeks, I started to write my diary again. I began by writing the days events in bullet points in capital letters (writing in upper case capitals was easier than writing in lower case letters). I then progressed to writing the whole day’s events but all in capital letters. On May 19, I started writing my diary “normally” again (i.e., in sentence case rather than in capital letters). I use the word “normally” advisedly. I’m still very slow writing with a pen and it’s not the most legible, but any activity I do with my hands I still call “therapy”. As I type this, I still do not have full functionality in either of my hands and I have resigned myself to the fact that I never will.

You can read Part 1 of this blog here.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Spinal rap: A brief look at my surgical recovery (so far) – Part 1

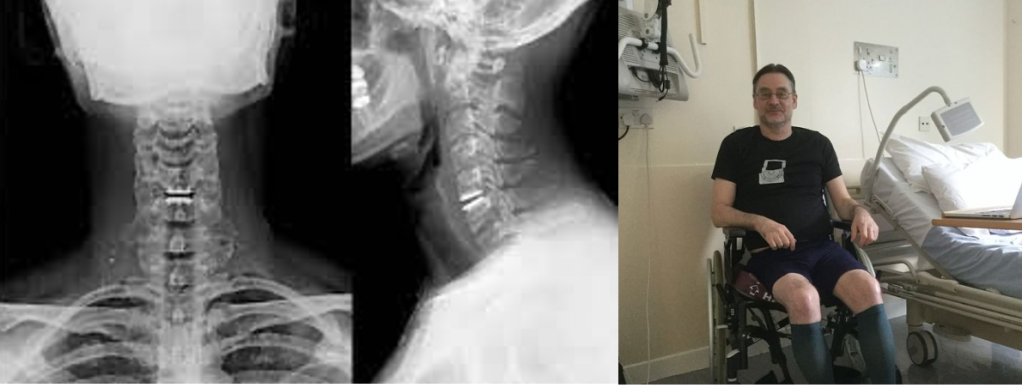

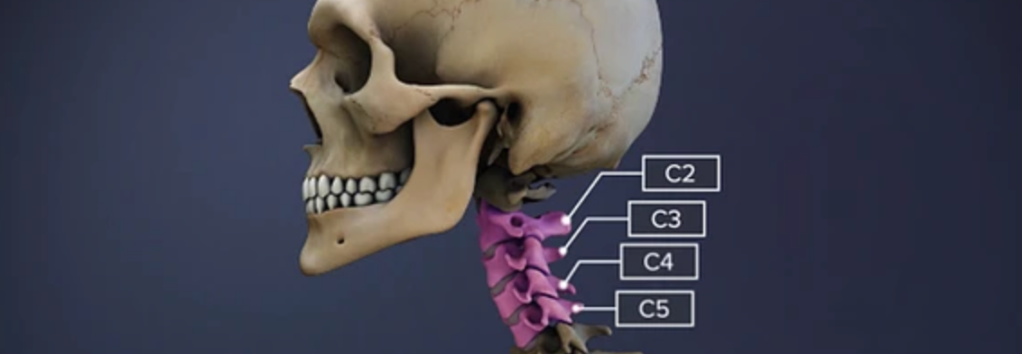

On April 15 I had an operation to decompress my spinal cord and to have the C5 disc in my neck replaced with a new titanium disc. I ended up in hospital for 67 days. Here’s the back story (no pun intended).

For the past 18 years I have lived with a compressed spinal cord. Although I had the condition since 2003, it wasn’t diagnosed until an MRI scan in 2007. The scan showed that the C5 disc in my neck was completely herniated and that the disc was pressing directly onto my spinal cord causing hundreds of electric shocks every single day. I was prescribed daily amitriptyline which significantly reduced the number of shocks I felt. I was also prescribed heavy duty painkillers (dihydrocodeine) but I soon realised that work was the best analgesic in the world. Instead of taking up to four doses of dihydrocodeine every day, I worked (and worked). I rarely took more than four doses of dihydrocodeine a year let alone a day. I was also given details of an operation I could have but just the very thought of it scared me – especially because of the risk of being left paralysed from the neck or chest down. I was told to come back if I changed my mind about having an operation.

I am not 100% sure what caused the complete herniation of the disc in my neck but I suspect it was a minor traffic collision I was involved in at the beginning of November 2003. I was sitting on the front seat on the top floor of a double decker bus when a taxi crashed into the right-hand side of the bus and I was propelled forward onto the bus’s front window where my head hit the glass window, smashed the glasses I was wearing, and left me concussed. I was highly stressed that day because I was on my way to have a CT scan to look at swollen lumps in my throat for suspected Hodgkin’s or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Later that week I had a lymphadenectomy and the biopsy showed that I didn’t have cancer but was diagnosed with toxoplasma lymphadenitis. It was after this operation that I began to get the constant daily electric shocks (over 100 a day) every time I moved my neck. I assumed that the constant electric shocks were as a result of my operation but I was later told that the shocks were being caused by a compressed spinal cord and that my lymphadenectomy was not the cause.

Over the next decade or so, the pain caused the constant compression of my spinal cord got progressively worse. Walking became increasingly difficult but I used excessive work as the strategy to suppress the increasing physical pain. In short, work became the perfect distractor task. When I was 100% cognitively engaged (e.g., giving a paper or teaching, writing or editing papers, etc.) I was in no pain whatsoever. I returned to the workaholic tendencies that I had before I had children. One of my consultants also described me as having “unspent youthfulness” which masked my medical condition for years.

The lifestyle I was leading in the years leading up to my operation probably didn’t help. I was travelling excessively averaging 20-25 overseas trips a year for conferences, consultancy, and research meetings. Walking became increasingly difficult as I was unable to lift my right foot properly. During 2019, I had a number of really bad falls abroad (tripping over because my right foot wouldn’t lift) including three in Abu Dhabi and a couple in Auckland which left me with horrendous bursitis on both of my elbows.

During the lockdown period, my health deteriorated badly. I was not globe-trotting anymore and I was housebound for over a year. My working life (and social life) became increasingly sedentary. I was doing everything from home including all my teaching. I had not stepped foot in my university office since the end of February 2020 (and still haven’t).

In August 2020, I saw one of my consultants and told him that my health condition had got significantly worse and that I now wanted the operation. However, because my surgery was classed as ‘elective’ as opposed to ‘urgent’ a date for surgery never came as the Nottingham hospitals were full of very ill COVID-19 patients. At one point during the pandemic, Nottingham was the UK city with the most COVID-19 infections. By February 2020 I could hardly walk and was becoming increasingly immobile. I rang my consultant’s secretary every week asking if I could have an appointment. I finally got one at the end of March 2021 and after seeing how bad my mobility was, I got an operation date very quickly. Thursday April 15, 2021. I was told by my consultant who was performing the surgery that he expected my to be back home the next day if the surgery was successful.

I have to be honest and say that the operation still scared me. Although there was a small chance of dying, that didn’t worry me. It was the thought of waking up paralysed which dominated my thoughts for over a week prior to the operation. Loss of limb use. Loss of job and livelihood Loss of identity. Loss of salary. There are many risks with any operation but spinal surgery carries many extra risks. I was told that some of the consequences could be eating and drinking difficulties and voice loss (as they would be carrying out the surgical procedure through the front of my neck and having to decompress my spinal cord by going via my trachea and oesophagus). I told my consultant that I would rather be dead than paralysed from the chest or neck down.

As the day of the operation approached, I again used work to block out my fears and negative thoughts. On April 15, my partner dropped me off at the hospital at 7am in the morning. Before my operation I had talks with the anaesthetist and one of the surgical team. I then had to sign the consent form which included a very long list of all the things that could go wrong. However, the weeks prior to my operation were surviving not living. I felt I was in the last chance saloon.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

To infinity (and beyond): The benefits of endless running videogames

Last week I was contacted by a journalist at the Red Bulletin Magazine who was “looking for an expert in gaming psychology to talk to for a piece on the mental benefits of endless running games, i.e. ‘the gameplay building strong reward learning in players’. It should be a fun and practical guide…Just let me know if you’d be interested.” I was interested. I had been teaching in the morning so I didn’t get the email until a couple of hours after it had been sent. I scribbled down a few notes, got back in touch, but by the time I did, the journalist had already interviewed someone else for the feature. Since I’d already made a few bullet points, I thought I would use them for the basis of a blog. (I really don’t like things going to waste).

Although much of my research examines problematic gaming, I am not anti-gaming (and never have been), and I have published many papers on the benefits of gaming including therapeutic benefits, educational benefits, and psychological (cognitive) benefits (see ‘Further reading’ below). Some of you reading this may not know what endless running games are, so here is the Wikipedia definition from its entry on platform games:

“‘Endless running’ or ‘infinite running’ games are platform games in which the player character is continuously moving forward through a usually procedurally generated, theoretically endless game world. Game controls are limited to making the character jump, attack, or perform special actions. The object of these games is to get as far as possible before the character dies. Endless running games have found particular success on mobile platforms. They are well-suited to the small set of controls these games require, often limited to a single screen tap for jumping. Games with similar mechanics with automatic forward movement, but where levels have been pre-designed, or procedurally generated to have a set finish line, are often called “auto-runners” to distinguish them from endless runners”.

Endless running games are incredibly popular and played by millions of individuals around the world (including myself on occasions). One of the best things about endless running games is that because they can be played on smartphones and other small hand-held devices they can be played anywhere at any time. Like any good game, the rules are easy to understand, the gameplay is deceptively simple, but in the end, it takes skill to succeed. The simplicity of endless running games is one of the key reasons for their global success in terms player numbers. For successful games, the mechanics should be challenging but not impossible. Such games can lead to what has been described as a state of ‘flow’ (coined by Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi in his seminal books Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience [1990] and Flow: The Psychology of Happiness [1992]).

With the flow experience, a game player derives intense enjoyment by being immersed in the gaming experience, the challenges of the game are matched by the player’s skills, and the player’s sense of time is distorted so that time passes without it being noticed. For some video game players, this may then mean repeatedly seeking out similar experiences on a regular basis to the extent that they can escape from their concerns in the ‘real world’ by being continually engrossed in a flow-inducing world. However, something like flow – viewed largely as a positive psychological phenomenon – may be less positive in the long-term for some video game players if they are craving the same kind of emotional ‘high’ that they obtained the last time that they experienced flow when playing a video game.

Flow has been proposed (by Jackson and Eklund, 2006) as comprising nine elements that include: (i) striking a balance between the challenges of an activity and one’s abilities; (ii) a merging of performance of actions with one’s self-awareness; (iii) possessing clear goals; (iv) gaining unambiguous feedback on performance; (v) having full concentration on the task in hand; (vi) experiencing a sense of being in control; (vii) losing any form of self-consciousness; (viii) having a sense of time distorted so that time seems to speed up or slow down; and (ix) the undergoing of an auto-telic experience (e.g., the goals are generated by the person and not for some anticipated future benefit). Endless running games are one of many types of videogame that can result in ‘flow’ experiences (which for the vast majority of gamers is going to result in something more positive (psychologically) than negative.

There are many studies showing that playing video games can improve reaction times and hand-eye co-ordination. For example, research has shown that spatial visualisation ability, such as mentally rotating and manipulating two- and three-dimensional objects, improves with videogame playing. Again, endless running videogames rely very heavily on hand-eye co-ordination and fast reaction to on-screen events. In this specific area, I see endless running games as having nothing but positive benefits in terms of improving hand-eye co-ordination skills, reflexes, and attention spans.

Although I’m not a neuroscientist or a neuropsychologist, I know that on a neurobiological level, when we engage in pleasurable activity, our bodies produce its own opiate-like neurochemicals in the form of endorphins and dopamine. The novelty aspects of endless running games will for many players result in the production of neurochemical pleasure which is rewarding and reinforcing for the gamer.

I also believe that endless running games have an appeal that crosses many demographic boundaries, such as age, gender, ethnicity, or educational attainment. They can be used to help set goals and rehearse working towards them, provide feedback, reinforcement, self-esteem, and maintain a record of behavioural change in the form of personal scores. Beating one’s own personal high scores or having higher scores than our friends and fellow gamers can also be psychologically rewarding.

Because video games can be so engaging, they can also be used therapeutically. For instance, research has consistently shown that videogames are excellent cognitive distractors and can help reduce pain. Because I have a number of chronic and degenerative health conditions, I play a number of cognitively-engrossing casual games because when my mind is 100% engaged in an activity I don’t feel any pain whatsoever. Again, endless running games tick this particular box for me (and others). Also, on a personal level, I am time-poor because I work so hard in my job. Endless running games are ideal for individuals like myself who simply don’t have the time to engage in playing massively multiplayer online games that can take up hours every day but will quite happily keep myself amused and pain-free on my commute into work on the bus.

As I have pointed out in so many of my research papers and populist writings over the years, is that the negative consequences of playing almost always involve a minority of individuals that are excessive video game players. There is little evidence of serious acute adverse effects on health from moderate play, endless running games included.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row

Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1992). Flow: The psychology of happiness. London: Random House.

Griffiths, M.D. (2002). The educational benefits of videogames Education and Health, 20, 47-51.

Griffiths, M.D. (2003). The therapeutic use of videogames in childhood and adolescence. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 8, 547-554.

Griffiths, M.D. (2004). Can videogames be good for your health? Journal of Health Psychology, 9, 339-344.

Griffiths, M.D. (2005). Video games and health. British Medical Journal, 331, 122-123.

Griffiths, M.D. (2005). The therapeutic value of videogames. In J. Goldstein & J. Raessens (Eds.), Handbook of Computer Game Studies (pp. 161-171). Boston: MIT Press.

Griffiths, M.D. (2010). Adolescent video game playing: Issues for the classroom. Education Today: Quarterly Journal of the College of Teachers, 60(4), 31-34.

Griffiths, M.D. (2019). The therapeutic and health benefits of playing videogames. In: Attrill-Smith, A., Fullwood, C. Keep, M. & Kuss, D.J. (Eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Cyberpsychology. (pp. 485-505). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Griffiths, M.D., Kuss, D.J., & Ortiz de Gortari, A. (2017). Videogames as therapy: An updated selective review of the medical and psychological literature. International Journal of Privacy and Health Information Management, 5(2), 71-96.

Jackson, S.A. & Eklund, R.C. (2006). The flow scale manual. Morgan Town, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

Nuyens, F., Kuss, D.J., Lopez-Fernandez, O., & Griffiths, M.D. (2019). The experimental analysis of non-problematic video gaming and cognitive skills: A systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 389-414.

Turning over a new belief: The psychology of superstition

According to Stuart Vyse in his book Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition, the fallibility of human reason is the greatest single source of superstitious belief. Sometimes referred to as a belief in “magic”, superstition can cover many spheres such as lucky or unlucky actions, events, numbers, and/or sayings, as well as a belief in astrology, the occult, the paranormal, or ghosts. It was reported by Colin Campbell in the British Journal of Sociology, that approximately one third of the U.K. population are superstitious. The most often reported superstitious behaviours are (i) avoiding walking under ladders, (ii) touching wood, and (iii) throwing salt over one’s shoulder.

My background is in the gambling studies field, so as far as I am concerned, no superstitions are based on facts but are based on what I would call ‘illusory correlations’ (e.g., noticing that the last three winning visits to the casino were all when you wore a particular item of clothing or it was on a particular day of the week). While the observation may be fact-based (i.e., that you did indeed wear a particular piece of clothing), the relationship is spurious.

Superstition can cover many spheres such as lucky or unlucky actions, events, numbers, and/or sayings. A working definition within our Western society could be a belief that a given action can bring good luck or bad luck when there are no rational or generally acceptable grounds for such a belief. In short, the fundamental feature underlying superstitions is that they have no rational underpinnings.

There is also a stereotypical view that there are certain groups within society who tend to hold more superstitious beliefs than what may be considered the norm. These include those involved with sport, the acting profession, miners, fishermen, and gamblers – many of whom will have superstitions based on things that have personally happened to them or to those they know well. Again, these may well be fact-based but the associations they have experienced will again be illusory and spurious. Most individuals are basically rational and do not really believe in the effects of superstition. However, in times of uncertainty, stress, or perceived helplessness, they may seek to regain personal control over events by means of superstitious belief.

One explanation for how we learn these superstitious beliefs has been suggested by the psychologist B.F. Skinner and his research with pigeons. He noted in a 1948 issue of the Journal of Experimental Psychology, that while waiting to be fed, pigeons adopted some peculiar behaviours. The birds appeared to see a causal relationship between receiving the food and their own preceding behaviour. However, it was merely coincidental conditioning. There are many analogies in the human world – particularly among gamblers. For instance, if a gambler blows on the dice during a game of craps and subsequently wins, the superstitious belief is reinforced through the reward of winning. Another explanation is that as children we are socialized into believing in magic and superstitious beliefs. Although many of these beliefs dissipate over time, children also learn by watching and modelling their behaviour on that of others. Therefore, if their parents or peers touch wood, carry lucky charms, and do not walk under ladders, then children are more likely to imitate that behaviour, and some of these beliefs may be carried forward to later life.

In a paper published in Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, Peter Darke and Jonathan Freedman (1997) suggested that lucky events are, by definition, determined entirely by chance. However, they go on to imply that, although most people would agree with this statement on an intellectual level, many do not appear to behave inaccordance with this belief. In his book Paradoxes of Gambling Behaviour, Willem Wagenaar (1988) proposed that in the absence of a known cause we tend to attribute events to abstract causes like luck and chance. He goes on to differentiate between luck and chance and suggests that luck is more related to an unexpected positive result whereas chance is related to surprising coincidences.

Bernard Weiner, in his book An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotion, suggests that luck may be thought of as the property of a person, whereas chance is thought to be concerned with unpredictability. Gamblers appear to exhibit a belief that they have control over their own luck. They may knock on wood to avoid bad luck or carry an object such as a rabbit’s foot for good luck. Ellen Langer argued in her book The Psychology of Control that a belief in luck and superstition cannot only account for causal explanations when playing games of chance, but may also provide the desired element of personal control.

In my own research (with Carolyn Bingham) into superstition among bingo players published in the Journal of Gambling Issues, it was clear that a large percentage of bingo players we surveyed reported beliefs in luck and superstition. However, the findings were varied, with a far greater percentage of players reporting everyday superstitious beliefs rather than beliefs concerned with bingo. Whether or not players genuinely believed they had control over luck is unknown. Having superstitious beliefs may be simply part of the thrill of playing.

Dr Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Campbell, C. (1996). Half-belief and the paradox of ritual instrumental activism: A theory of modern superstition. British Journal of Sociology, 47(1), 151–166.

Darke, P. R., & Freedman, J. L. (1997). Lucky events and beliefs in luck: Paradoxical effects on confidence and risk-taking. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 378–388.

Griffiths, M.D. & Bingham, C. (2005). A study of superstitious beliefs among bingo players. Journal of Gambling Issues, 13. Located at: http://jgi.camh.net/index.php/jgi/article/view/3680/3640

Langer, E. J. (1983). The psychology of control. London: Sage.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). “Superstition” in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 168–172.

Thalbourne, M.A. (1997). Paranormal belief and superstition: How large is the association? Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 91, 221–226.

Vyse, S. A. (1997). Believing in magic: The psychology of superstition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wagenaar, W. A. (1988). Paradoxes of gambling behaviour. London: Erlbaum.

Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: Springer-Verlag

Nailed it: A brief look at onychophilia

In a previous blog, I looked at fingernail fetishism. Since writing that article, I’ve had a few individuals get in touch with me to say that they had very specific fingernail fetishes (such as a keen interest in very long nails). As the Kinkly website notes:

“A fingernail fetish can hinge on the nail color, texture, or length. If the fetish hinges on long nails, the fetish is sometimes referred to as onychophilia. For the fingernail fetishist the excitement is in the details, so nail art is given special attention”.

However, a really short article on ‘Lady Zombie’s World of Pain, Pleasure and Sin’ website also notes that onychophilia as a fingernail fetish but says it only refers to long nails (rather than nails more generally):

“Onychophilia is a fetish for extremely long nails (either real or fake) and/or painted fingernails. As with all fetishes, preferences vary! While some fetishists say, ‘The longer, the better,’ many others find them to be repulsive after a certain length”.

In my previous article I mentioned the the only specific case of fingernail fetishism that I found in the academic literature was a 1972 paper in the American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, by Dr. Austin McSweeny who successfully treated a young male fingernail fetishist using hypnosis (although other sexologists such as Willem Stekel and Martin Kafka had mentioned such a fetish in passing). The same case study was cited by Dr. Jesse Baring in a blog on fingernail fetishism for Scientific American. He noted:

“He could [only] become sexually aroused and experience penile erection by seeing or fantasizing the fingernails of a woman as they were being bitten by her. Occasionally, the mere sight of a woman’s severely bitten fingernails would cause the patient to experience a spontaneous erection … When the patient experienced the proper fetish situation, he could masturbate to the point of ejaculation and experience gratification. This was his only means of expressing his sex drive…The psychotherapist’s request for the man to picture heterosexual intercourse or a vagina in his mind’s eye was enough to make him vomit”.

A 2019 article by Stephen Alexander (‘Onychophilia: Two types of nail fetish’) notes that fingernail fetishes are subsumed within ‘hand partialism’ (which can arguably include other fetishes I have examined including ‘handwear fetishism’ and ‘hands on hips fetishism’). Alexander asserts:

“I think that [fingernail fetishism] deserves critical attention in its own right. For the nails are not like any other part of the hand in that they are not composed of living material; they are made, rather, of a tough protective protein called alpha-keratin. D. H. Lawrence [in his 1963 essay ‘Why the novel matters’] describes his fingernails as ‘ten little weapons between me and an inanimate universe, they cross the mysterious Rubicon between me alive and things […] which are not alive, in my own sense’. Thus, I think there’s something in the claim that what nail (and hair) fetishists are ultimately aroused by is death; that they are, essentially, soft-core necrophiles. Having said that, the human nail as a keratin structure (known as an unguis) is closely related to the claws and hooves of other animals, so I suppose one could just as legitimately suggest a zoosexual origin to the love of fingernails”.

To support his claim that fingernail fetishists are “soft-core necrophiles”, Alexander noted that there had been a recorded case in the 1963 book Perverse Crimes in History: Evolving concepts of sadism, lust-murder, and necrophilia – from ancient to modern times (by R.E.L. Masters and Eduard Lee) where “an illicit lover derived pleasure from eating the nail trimmings of corpses (necro-onychophagia), thereby lending support to the theory that nail fetishism has a far darker and more ghoulish undercurrent”.

I also learned in Alexander’s article that there is another related paraphilia – amychophilia – which refers to sexual arousal from being scratched (or as Alexander puts it: “a love of the pain [fingernails] can inflict, when grown long and sharp”). I went and checked if amychophilia was in my ‘go to’ book on paraphilias (i.e., Dr. Anil Aggrawal’s Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects of Sexual Crimes and Unusual Sexual Practices) – and it was. Dr. Aggrawal defines amychophilia as “deriving sexual pleasure from being scratched” which technically could mean sexual arousal from being scratched by things other than fingernails (e.g., toenails, back-scratcher) although scratching for most people will be synonymous with fingernail scratching. Given these definitions, I would argue that amychophilia is more akin to masochism than onychophilia because the root of amychophilia is in the feeling provided rather than what is doing the scratching. Alexander also quotes at length from Daphne du Maurier’s short story ‘The Little Photographer’ (from The Birds and Other Stories) and says that one scene in the book describes onychophilia in “fetishistic detail”. (I won’t reproduce it here but you can check it out in Alexander’s online article here).

Which brings me to the final article I came across on onychophilia by Liz Lapont on The Naked Advice website. She was writing in response to an email she had received:

“I’m a guy with a sexual fetish for long fingernails (not too long, usually the length that people get when they get their nails done). I beat off to pictures of nails and I have conversations with female friends about their nails. I wanted to know if you can make a video about this type of fetish. Seeing as not a lot of people talk about or show interest in this fetish, am I weird?”

Lapont replies that the fetish is both atypical and uncommon but not weird (“as in creepy and in need of psychiatric help”). My own take is that this is a non-normative sexual behaviour but agree with Lapont that there is nothing to worry about if the behaviour causes no problems in the individuals’ lives. She concludes by saying:

“Consult any list of the most common sexual fetishes and nails don’t crack the top 10. However it’s not unheard of, and toenails are often an associated turn-on for men with a fetish for feet. The clinical term for a fingernail fetish is onychophilia. For some, it’s the act of biting the fingernails that turn them on. For others, it might be their extreme length that is most erotic. Hands and nails play a big role even during the most vanilla sex in the world…So it’s not a stretch to see how for some men, fixating on fingernails would be IT for them”.

Dr Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Aggrawal A. (2009). Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects of Sexual Crimes and Unusual Sexual Practices. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Alexander, S. (2019). Onychophilia: Notes on two types of nail fetish. Torpedo The Ark. March 18. Located at: http://torpedotheark.blogspot.com/2019/03/onychophilia-notes-on-two-types-of-nail.html

Baring, J. (2013). Bite those nails, baby: A “quick” tale of fingernail Fetishism. Scientific American, August 14. Located at: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/bering-in-mind/bite-those-nails-baby-a-e2809cquicke2809d-tale-of-fingernail-fetishism/

Baring, J. (2013). Perv: The Sexual Deviant In All Of Us. New York: Scientific American/Farrar, Strauss & Giroux.

Kafka, M. (2010). The DSM diagnostic criteria for fetishism. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 357-362.

Kinkly (2020). Fingernails fetish. Located at: https://www.kinkly.com/definition/6664/fingernails-fetish

Lady Zombie (2011). Onychophilia – Long nail fetish. February 4. Located at: http://ladyzombienyc.blogspot.com/2011/02/onychophilia-long-nail-fetish.html

Lapont, L. (2017). Fingernails aren’t just great for back scratching. The Naked Advice, August 21. Located at: https://thenakedadvice.wordpress.com/2017/08/21/fingernails-arent-just-for-great-back-scratching/

Lawrence, D.H. (1985). Why the novel matters. In Steele, B. (Ed.), Study of Thomas Hardy and Other Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Masters, R.E., & Lea, E. (1963). Perverse crimes in history: Evolving concepts of sadism, lust-murder, and necrophilia, from ancient to modern times. New York: Julian Press.

McSweeny, A.J. (1972). Fetishism: Report of a case treated with hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 15, 139-143.

Scorolli, C., Ghirlanda, S., Enquist, M., Zattoni, S. & Jannini, E.A. (2007). Relative prevalence of different fetishes. International Journal of Impotence Research, 19, 432-437.

Stekel, W. (1952). Sexual Aberrations: The Phenomena of Fetishism in Relation to Sex (Vol. 1) (Trans., S. Parker). New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Stekel, W. (1952). Sexual Aberrations: The Phenomena of Fetishism in Relation to Sex (Vol. 1) (Trans., S. Parker). New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Reading by example: The books that inspired my career

This Christmas I managed to do a lot of book reading (most of it being David Bowie-related) and my favourite read was John O’Connell’s Bowie’s Books: The Hundred Literary Heroes Who Changed His Life (which If I’m nit-picking should actually be the 98 heroes because George Orwell and Anthony Burgess make two appearances each on the list), followed by Will Brooker’s Why Bowie Matters (a book I wish I had wrote because it was written by a Professor of Film and Cultural Studies and is a loose account of an academic spending a whole year trying to live like David Bowie as a piece of research). I also love lists so I thought I’d kick off the New Year with a list of the books that have shaped my academic life. This list was first published by The Psychologist (in 2018) but this blog may give my list a wider readership.

Excessive Appetites: A Psychological View of the Addictions (by Jim Orford)

One of the most influential books on my whole career is Jim Orford’s seminal book Excessive Appetites that explored many different behavioural addictions including gambling, sex, and eating (i.e., addictions that don’t involve the ingestion of psychoactive substances). Jim Orford’s books are always worth a read and he writes in an engaging style that I have always admired. It was by chance that I did my PhD at the University of Exeter (1987-1990) where Orford was working at the time and since 2005 we have published many co-authored papers together. While we can agree to disagree on some aspects of how and why people become addicted, Jim will continue to be remembered as a pioneer in the field of behavioural addiction.

The Psychology of Gambling (by Michael Walker)

If there’s one book I’d wish I had written myself, it is this one. I did my PhD on slot machine addiction in adolescence but this book was published shortly after I’d finished and beautifully summarises all the main theories and perspectives on gambling psychology. My PhD would have been a whole lot easier if this book had been published when I first started my research career! I got to know Michael quite well before his untimely death in December 2009 (and he was external PhD examiner to some of my PhD students), and one of my enduring images of him was walking around at gambling conferences with his book clutched in his hand. Some of my colleagues found that a little strange but if I’d have written a book that good I’d have it with me at such events all the time!

Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change (by William R. Miller and Stephen Rollnick)

I reviewed this book for the British Journal of Clinical Psychology (BJCP) back in the early 1990s and concluded by saying that it is a book that should be read by all therapists because its content can be applied to nearly all clinical situations and not just to those individuals with addictive behaviour problems. Motivational interviewing (MI) borrows strategies from cognitive therapy, client-centred counselling, systems theory, and the social psychology of persuasion, and the underlying theme of the book is the issue of ambivalence, and how the therapist can use MI to resolve it and allow the client to build commitment and reach a decision to change. In my most recent research I’ve used the basic tenets of MI in designing personalised messages to give to gamblers while they are gambling online in real time. I’ve now come to the conclusion 25 years after writing my BJCP review that anyone interested in enabling behavioural change should apply the tenets in this book to their work.

The Myth of Addiction (by John B. Davies)

Even though this book was published back in 1992, I still tell my current students that this is a ‘must read’ book. Davies takes a much researched area of social psychology (i.e., attribution theory) and applies it to addiction. The basic message of the book is that people take drugs because they want to and not because they are physiologically addicted. The whole book is written in a non-technical manner and is highly readable and thought provoking. I often use Davies’ term ‘functional attribution’ from this book in my teaching and writings on sex addiction, and apply it to celebrities who use the excuse of ‘sex addiction’ to justify their infidelities.

Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects of Sexual Crimes and Unusual Sexual Practices (by Anil Aggrawal)

Anyone that reads my blog will know that when it comes to the more bizarre side of sexual activity, my ‘go to’ book is Dr. Aggrawal’s book on unusual sexual practices. Others in the sexology field often look down their noses at this book but it is both enjoyable and informative and the kind of book that once you start reading you find it hard to put down again. A lot of academic books on sexual behaviour can be boring and/or impenetrable but this one is the polar opposite. The book also kick-started some of my own recently published research on sexual fetishes and paraphilias.

Small World (by David Lodge)

During my PhD, I remember watching the 1988 adaptation of David Lodge’s novel Small World. At the time, I had never heard of David Lodge but I went out and bought the book and was totally hooked. I then discovered that Small World was the second part of a ‘campus trilogy’ (preceded by Changing Places and followed by Nice Work). Since then I have bought every novel Lodge has ever published and he’s my favourite fiction writer (and I’ve bought and read some of his academic books on literary criticism). I love campus novels and through Lodge and devoured other university-based novels (including Malcolm Bradbury’s The History Man, Howard Jacobson’s Coming from Behind, and Ann Oakley’s The Men’s Room among my favourites).

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Aggrawal A. (2009). Forensic and Medico-legal Aspects of Sexual Crimes and Unusual Sexual Practices. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Brooker, W. (2019) Why Bowie Matters. London: William Collins.

Davies J. B. (1992). The Myth of Addiction. Reading: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Griffiths, M.D. (2018). My shelfie. The Psychologist: Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 31, 70.

Lodge, D. (1984). Small World. London: Secker & Warburg.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (1991). Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. New York: Guilford Press.

O’Connell, J. (2019). Bowie’s Books: The Hundred Literary Heroes Who Changed His Life. London: Bloomsbury.

Orford, J. (2001). Excessive Appetites: A Psychological View of the Addictions. Chichester: Wiley.

“I ink, therefore I am”: A brief look at ‘tattoo addiction’

“When I first told people back in 2016 that I was getting my first tattoo, the most common response I got from those who were already inked themselves was ‘You’re going to get addicted to getting tattoos’. I found this notion a little ridiculous – I was nervous enough just getting a small one on my ankle. I couldn’t imagine getting hooked on something that was not only expensive, but painful and permanent. Fast forward to 2019, and I’ve since gotten two more tattoos, each one progressively larger and more detailed, and I’m already planning my fourth, fifth, sixth, etc. As I was warned, I have indeed gotten hooked. For me, it’s both because I love how it makes me feel about my body, and because I’ve gotten to discover a new form of expression in my mid-30s. According to a 2018 report from Statista, roughly 46 percent of Americans have at least one tattoo, and 30 percent of these people have two or three –19 percent have up to four or five. Clearly, other people love getting inked just as much as I do. But while tattoos can be fun to have, are they actually addictive?

This opening quote is by Amy Semigran, a journalist who interviewed me earlier this year for an article she was writing on addictions to tattoos for the online magazine Mic (‘Are tattoos really addictive? There’s a reason you keep coming back for more’). Regular readers of my blog will be aware that I’ve written various articles on the psychology of tattoos over the years including articles on stigmatophilia (sexual arousal from a partner who is marked or scarred in some way, which can also include body tattoos), the use of extreme tattooing in films, a look at the TV programme ‘My Tattoo Addiction’, and an article on whether having tattoos makes women more sexually attractive.

In my interview, I told Semigran that in order for a person’s behaviour to be deemed an addiction, it needs to meet my six specific criteria: salience (where tattooing becomes the most important thing in a person’s life), mood modification (e.g., the euphoric feelings that accompany tattooing), tolerance (the gradual build-up of tattooing with the individual spending more and more time engaged in tattooing), withdrawal symptoms (negative psychological and/or physical consequences as a result of not being able to get tattooed such as extreme moodiness or irritability), conflict (tattooing compromising other areas of the individual’s life such as personal relationships and education/occupation), and relapse (returning to tattooing after a period of abstinence). Therefore, I told Semigran that tattooing does not meet my criteria for addiction. I also added that while many behaviours can become impulsive, addiction relies on constant rewards or reinforcement. Alcoholics, gambling addicts, or drug addicts feed their habits with frequent rewarding experiences (at least in the short-term) but even the most heavily tattooed people are not engaging in the behaviour regularly.

However, it is feasible that tattooing could be a behaviour that results in constant preoccupation (e.g., constantly thinking about getting the next tattoo, looking at tattoo designs, reading tattooing magazines, talking with other heavily tattooed individuals and sharing experiences, working as a tattooist, etc.). However, constantly being preoccupied by tattooing is (in itself) not a problem, unless of course it starts to cause serious conflict with other day-to-day activities. Semigran also interviewed Dr. Daniel Selling (a psychologist at Williamsburg Therapy Group in New York) for her article. He was quoted as saying:

“The word addiction in the context of tattoos is misused…while you can’t have a tattoo addiction, per se, it can be a dependence where you feel some elements of need and withdrawal…and perhaps spend too much time or money getting work…Being tattooed can also lead to an adrenaline rush of sorts. It’s the body tolerating annoyance and pain coupled with excitement and change”.

I agree that some people can spend too much time or money or spend money they don’t have on getting tattoos, but this is not addiction (and I would also argue that it is not dependence either). For many people, getting tattoos might be more of a passion than a problem, and there is nothing wrong with being passionate about what you do. I am passionate about work and some people describe me as being addicted to work or of being a ‘workaholic’ but given there are almost no negative consequences of me working hard and loving my job, it certainly can’t be viewed as an addiction.

As Semigran pointed out in her article, for many people, their passion and interest in tattooing is something that enhances their lives rather than interferes with it (this is exactly the same as my assertion – published in a 2005 issue of the Journal of Substance Use) that healthy excessive enthusiasms add to life whereas addictions take away from it. Semigran interviewed Lisa Orth, a Los Angeles-based tattoo artist Lisa Orth who has around 100 tattoos). She said:

“It’s an incredible feeling to be able to permanently customize yourself with artwork. [The] feeling of self-expression can be an empowering experience…It’s one of the main reasons [my] clients come back again and again. Tattooing can be a way of engaging with, and taking possession of, one’s body in an active way…[It] can allow people to define themselves visually in a way that forces the observer to see a person as they most authentically see themselves. That’s a big draw (so to speak) for those who repeatedly get inked…Getting tattooed is one of the remaining rituals in our culture that are physical, mental and emotional challenges, where you come out transformed on the other side”.

Again, this explanation has nothing to do with addiction and everything to do with self-identity and passion. Many addiction psychologists, would also add that if he behaviour causes harm or injury to the individual, it may also be a sign or symptom of possible addiction. However, Semigran quoted American psychologist, Dr. Tracy Alderman from an article she wrote for Psychology Today examining the extent to which tattooing and body piercings can be classed as self-harm.

“[E]njoying a rush is different than participating in self-harm. Since tattooing is a needle penetrating skin, that can potentially feed someone’s desire to feel pain or change their appearance due to unhappiness with themselves…Once in a while there will be cases in which piercing and/or tattoos do fit the definition of self-injury. But overwhelmingly,self-injury is a distinct behavior, in definition, method and purpose, from tattooing and piercing”.

I read Dr. Alderman’s article and her views mirror my own when it comes to the psychology of tattooing:

“[A] main issue separating self-injurious acts from tattoos and piercings is that of pride. Most people who get tattooed and/or pierced are proud of their new decorations. They want to show others their ink, their studs, their plugs. They want to tell the story of the pain, the fear, the experience. In contrast, those who hurt themselves generally don’t tell anyone about it. Self-injurers go to great lengths to cover and disguise their wounds and scars. Self-injurers are not proud of their new decorations”.

Semigran also quoted Dr. Suzanne Phillips who recently wrote an article for PsychCentral entitled ‘Tattoos after trauma-do they have healing potential’. Dr. Phillips notes:

“[A tattoo being used] to register a traumatic event is a powerful re-doing…It starts at the body’s barrier of protection, the skin, and uses it as a canvas to bear witness, express, release and unlock the viscerally felt impact of trauma”.

There’s no doubt that tattooing has become part of mainstream culture over the past two decades and there are a number of scholars who claim in the scientific literature that getting tattoos can be potentially addictive (such as Dr. Ivan Sosin; Dr. Allyna Murray and Dr. Tanya Tompkins; see ‘Further Reading’ below) but based on my own addiction criteria I remain to be convinced. However, whenever I think about the psychology of tattooing, I am always reminded of the saying: “Tattoos are like potato chips … you can’t have just one”.

Dr. Mark Griffiths, Distinguished Professor of Behavioural Addiction, International Gaming Research Unit, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Further reading

Alderman, T. (2009). Tattoos and piercings: Self-injury? Psychology Today, December 10. Located at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/nz/blog/the-scarred-soul/200912/tattoos-and-piercings-self-injury?amp

Griffiths, M.D. (1996). Behavioural addictions: An issue for everybody? Journal of Workplace Learning, 8(3), 19-25.

Griffiths, M.D. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10, 191-197.

Kovacsik, R., Griffiths, M.D., Pontes, H., Soós, I., de la Vega, R., Ruíz-Barquín, R., Demetrovics, Z., & Szabo, A. (2019). The role of passion in exercise addiction, exercise volume, and exercise intensity in long-term exercisers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9880-1

Murray, A. M., & Tompkins, T. L. (2013). Tattoos as a behavioral addiction. Science and Social Sciences, Submission 26. Located at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/studsymp_sci/2013/all/26

Phillips, S. (2019). Tattoos after trauma-do they have healing potential? PsychCentral, March 27. Located at: https://blogs.psychcentral.com/healing-together/2012/12/tattoos-after-trauma-do-they-have-healing-potential/

Semigran, A. (2019). Are tattoos really addictive? There’s a reason you keep coming back for more. Mic, July 3. Located at: https://www.mic.com/p/are-tattoos-really-addictive-theres-a-reason-you-keep-coming-back-for-more-18166085

Sosin, I. (2014). EPA-0786-Tattoo as a subculture and new form of substantional addiction: The problem identification. European Psychiatry, 29, Supplement 1, 1.

Szabo, A., Griffiths, M.D., Demetrovics, Z., de la Vega, R., Ruíz-Barquín, R., Soós, I. &Kovacsik, R. (2019). Obsessive and harmonious passion in physically active Spanish and Hungarian men and women: A brief report on cultural and gender differences. International Journal of Psychology, 54, 598-603.